As the son of a first generation Trinidadian Canadian, born in the concrete suburbia of Toronto, I was raised in an era where the NHL’s hapless Toronto Maple Leafs struggled to maintain competitive relevance and where the Edmonton Oilers wielded insurmountable dominance. Despite the ineptitude of my hometown club, I still slid across the parquet flooring of my low-rise apartment with mini-stick in hand, pretending to be the likes of Rick Vaive, Borje Salming, and of course, Grant Fuhr, the first Black player inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame.

After watching Soul On Ice: Past, Present and Future, a documentary by Damon Kwame Mason and speaking at-length with the budding filmmaker, it became apparent that many young Canadians of Afro-Caribbean heritage were similarly impassioned by the sport of hockey, and like myself, were unable to fully embrace the culture that many of their Anglo counterparts were able to enjoy.

In my household, the economics of the sport just didn’t make sense. At the rate I was growing, there was no possible way that we could afford the rising costs of equipment and registration fees. Swimming and soccer it was. So too, was this financial barrier an existing problem for Kwame, as he found himself relegated to sports that were less taxing on the pocketbook and readily accepted by darker complexioned kids.

The Black athlete’s athletic prowess in sports such as football, basketball and baseball has been widely acknowledged and heavily depicted in folklore, textbooks and the silver screen. However, such depiction of the Black athlete in hockey is close to non-existent. Mason questioned this glaring historical omission and decided to gather as much information about the Black hockey player with the intention of bringing to light an important part of our history in a sport so widely dominated by White athletes.

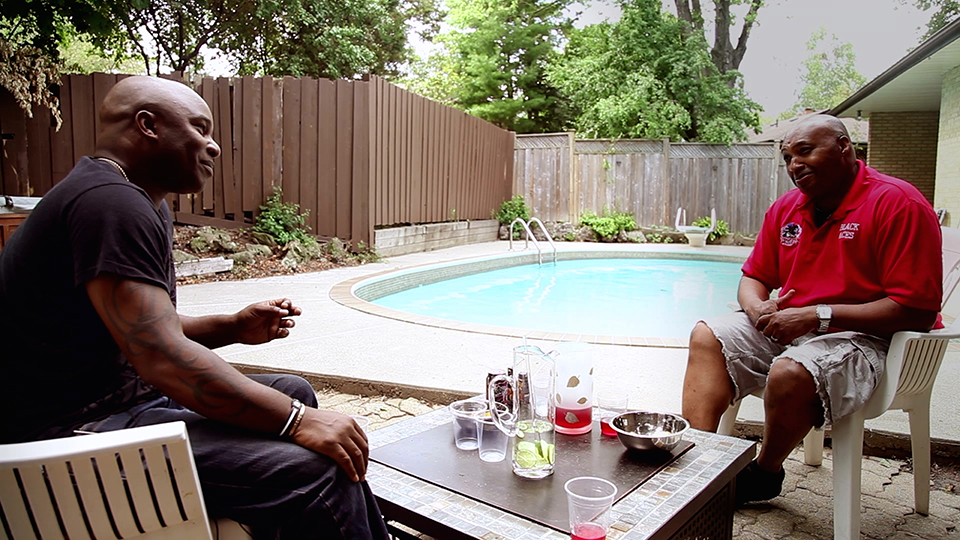

Having sojourned from Toronto’s urban diaspora to the arctic-like tundra of Alberta, and setting up shop as a radio host in Edmonton, Mason grew to become increasingly familiar with the local professional hockey scene and soon became a co-host of a weekly show with Black French Canadian and Oilers’ tough guy, Georges Laraque.

Through various conversations and random meetings with well-traveled former and current professional hockey players, coaches and supporters, Kwame was able to begin the makings of what would prove to be one of the most preeminent and vital Black sports documentaries of our time.

Soul on Ice: Past, Present and Future takes the viewer on a journey through time to when Blacks were not allowed to participate in sports with Whites and societal segregation based on race was a normality. Mason cleverly and seamlessly juxtaposes the roots of Black Canadian hockey with current and future players, as we are given a snapshot of the current state of Black hockey.

Its roots are firmly planted in the post-slavery, eastern region of Canada called Nova Scotia. The province, as the doc claims, was home to North America’s first professional all-Black hockey league – the Coloured Hockey League of the Maritimes – a league formed in 1895, when Black players were unable to suit up alongside their White counterparts.

The documentary takes the viewer on a journey of racially-charged games and events that have manifested a distinct increase in the level of involvement of young, Black men in the sport of hockey, which essentially has made the sight of brown-skinned young men in the rink more widespread and less of an anomaly. Although not quite the same participation in other major sports such as basketball and football, their presence is still felt throughout the NHL.

Soul On Ice: Past, Present and Future is not a documentary. It is an historical artifact whose story must never be silenced.

That presence is felt immensely in Montreal, as P.K. Subban, arguably the Canadiens’ best player has become the toast of the town. Subban is a polarizing figure whose bold personality borders between cockiness and confidence, but whose skill is undeniable.

Mason speaks at length with Subban’s family about their struggles and successes, however, P.K.’s presence is notably absent from the film.

It would be safe to assume that P.K. is the type of generational player that transcends race, colour or ethnicity. The mere fact that Subban is not seen as a Black hockey player to most, but rather a great, Norris Trophy-winning defenceman is a testament to the strides and progress that Black players have made in the sport. A sport that until just a few years ago, harnessed fans that spewed racial epithets from the stands to taunt and degrade non-White players who dared to lace up skates.

Mason delivers a poignant depiction of the racism that existed in the NHL, and the viewer is able feel the angst and discomfort felt by the likes of Black hockey pioneers such as Herb Carnegie and Willie O’Ree. Witnessing the accounts of what they endured on a nightly basis would surprise even the most open-minded, liberal Canadians who claim never to be racist because they call a few Black people in their lives “friends”.

Soul On Ice: Past, Present and Future is not a documentary. It is an historical artifact whose story must never be silenced. The story it tells is as Canadian as maple syrup and Tim Horton’s coffee and vital to Canada’s relevance. Kwame Mason should never get tired of taking bows for this production, as the insight provided in this production should not be limited to a PBS special on television, or a local film festival, but should be included in academic curriculum and historical mosaics throughout the country.

Photos from the film supplied by Pennant Media Group

1 Comment

Great story .. so many kids can relate to this.