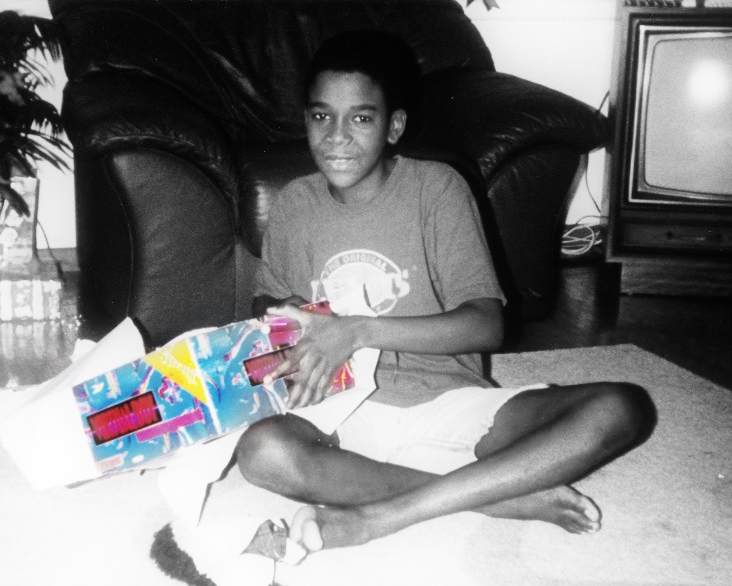

A lanky kid with the goofy grin on his face, the Levi’s branding matched with skintight jean shorts – a clear victim of ’90s nerd fashion – my former self.

A lot of poor decisions were made during those adolescent times, but few match up to the gifting of Nintendo’s infamous Virtual Boy on a Christmas Day, 1995. It was a device from hell that could produce bloodshot eyes like few things in life, but the word virtual plastered on its red and blue cardboard still personified an old and appealing promise; that oversized pairs of goggles could allow someone to go anywhere and be anyone through digital mimicry.

Films like 1992’s Lawnmower Man drove home the idea of virtual reality into my personal consciousness, as I also witnessed the word rapidly lose much of its meaning. Once it became part of the English language lexicon, terms like virtual pets, virtual fighter, virtual football, etc. cheapened the meaning of ‘virtual’ in the face of limiting technology.

Fast forward to the now, where the term ‘virtual’ is becoming more respected within the realm of possibility. Changes in opinion are producing devices like the virtual reality headset for 3D gaming, Oculus Rift, and visionaries like its original founder Palmer Luckey can sit comfortably knowing that his creation has transformed into a $75 million funded project/device, one also backed by social media titan Facebook. This newfound enthusiasm surrounding virtual reality (VR) equates to the good old days when the technology was seen as an attainable alternative to the rudimentary routines of real life.

It’s criminal to think that we’re downplaying a different kind of reality that has found its place within recent years.

As with all trends, other copycats have begun to follow suit in hopes of becoming the usurper to the VR throne. They come in names like Sony’s Project Morpheus and Steam’s HTC Vive with marketing campaigns that push a promise of more immersive gaming experiences. But through all the hububula around a long imagined dream of proper VR, it’s criminal to think that we’re downplaying a different kind of reality that has found its place within recent years.

“Gaming is just about the only industry that has the set of tools and skills needed for VR,” said Luckey. “At its core, VR is an extension of gaming. It’s the idea of digital parallel worlds, allowing people to communicate and do things in a virtual world. Most don’t spend the majority of their time playing games now, and I can’t see that changing with VR. Gaming is not the end game.”

When Palmer uttered these words in front of a group of forward thinkers, he may have done more of a push for augmented reality than he ever did for virtual reality. When thinking about the potential of these two takes on the real, one has to wonder why there’s a lack of excitement for the concept of an augmented world. While the technologies appear similar by design, it’s the methods that make them obviously different.

VR is much about total immersion. The real world is blocked from the user in favour of a programmed vision. It’s the feeling of being connected to something far away from what’s actually going on around you. There’s already a lack of practical application in this approach, as you’re a slave to what you see versus where you really are. Augmented reality, however, is a marriage of both worlds. Much like an overlay of information over existing information, it is the real world enhanced by computer-generated sensory inputs (think for example GPS).

While its earliest conventions can be dated back to the military, where jet fighters needed heads up displays projected in their direct field of vision for focus, products such as Google Glass and Microsoft’s HoloLens have become pioneers in pushing wearable augmented reality (AR) to the mainstream today. As a result, they’ve unfairly fallen victim to the fully tested experiences of devices like the Oculus Rift that serve to offer a completely different undertaking.

The true beauty of AR is in its ability to provide context. Up until now, mainstream AR has taken the form of limited smartphone applications that provide restaurant and pricing information, etc. in real time. With new hardware however, the scope of possibility has been broadened to a ridiculous dimension in its ability to provide context. Up until now, mainstream AR has taken the form of limited smartphone applications that provide restaurant and pricing information, etc. in real time. With new hardware however, the scope of possibility has been broadened to a ridiculous dimension.

Imagine a surgeon with holographic preoperative information about a patient – an infinite amount of knowledge at their beck and call. They can view a 3D reconstruction of organs through a visor that overlaps the eyes. A holographic overlay would act like a coating over the real life flesh of an individual. One can also visualize a world where vehicle repairmen with visible ass-cracks wouldn’t take advantage of car illiterates. Mechanical maintenance can become a self-taught affair as smarter cars begin to speak to devices like Google Glass or HoloLens in assessing personal damage, or providing manuals that can be visualized rather than be read. Let’s not forget the limitless possibilities when it comes to basic design. Construction and ideas can be realized through motion sensed interaction before being physically being touched in any way.

The potential for augmenting the reality we already live in is something that needs to be backed by the masses in equal measures to VR, because in all truth, the real world perfected is a world I’m sure many of us wouldn’t mind living in.

Hollywood has done plenty in displaying the practical possibilities through films like Minority Report all the way to Star Trek’s , which in all actuality was a version of augmented reality. Yet despite all this pop culture fluff, there still seems to be a superior level of enthusiasm for full-blown VR. The reasons can come down to preferences or functionality, but much of it can also find its root in a love for escapism. There is a whole industry of vices that thrive off of the concept, so the more of it, the better. Truly, what better escape can there be than the blocking out of an entire world in favour of an imagined one? In our efforts to do that, it’s important that we realize the practicalities of using the real world as a palette. The potential for augmenting the reality we already live in is something that needs to be backed by the masses in equal measures to VR, because in all truth, the real world perfected is a world I’m sure many of us wouldn’t mind living in.

Photos Courtesy of. Microsoft Corporation, Sony Entertainment, Valve Corporation and Wikipedia Commons.

@NoelRansome

Comments are closed.